Francesca Woodman, In and Out of Dress

Exploring a long-held fascination with aura and one of the most intriguing female photographers of the 20th century.

Have you ever been stopped in your tracks by a piece of art? Found yourself spending several minutes soaking in it, maybe trying to meld with it to somehow make it your own, even while it hangs static on the wall in front of you?

In viewing art in person, in a gallery or a studio, or on the walls of our homes, we not only experience art visually, but through the supernatural sense of aura.

In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction from 1935, Walter Benjamin explored the multifaceted concept of aura and the implications of the increasingly mechanical age in which he was living. He defined the aura as an effect of a work being uniquely present in time and space. The art necessitates a distance from its viewer, so that one may bask in the aura, to feel it on them like a ray of light or a gentle breeze. The churning out of reproductions, Benjamin argued, leads to the stripping away of the aura, as reproductions will never hold the presence of the original. At the time Benjamin was writing, he saw photography as one threat to the maintenance of the aura:

“The situations into which the product of mechanical reproduction can be brought may not touch the actual work of art, yet the quality of its presence is always depreciated.”

I’m curious if Benjamin were alive today if he would change his tune in regards to how he viewed photography (or cinema for that matter). In our world of rapidly increasing digital technology, the idea of analog photography and film prints have proven to maintain an aura of their own kind.

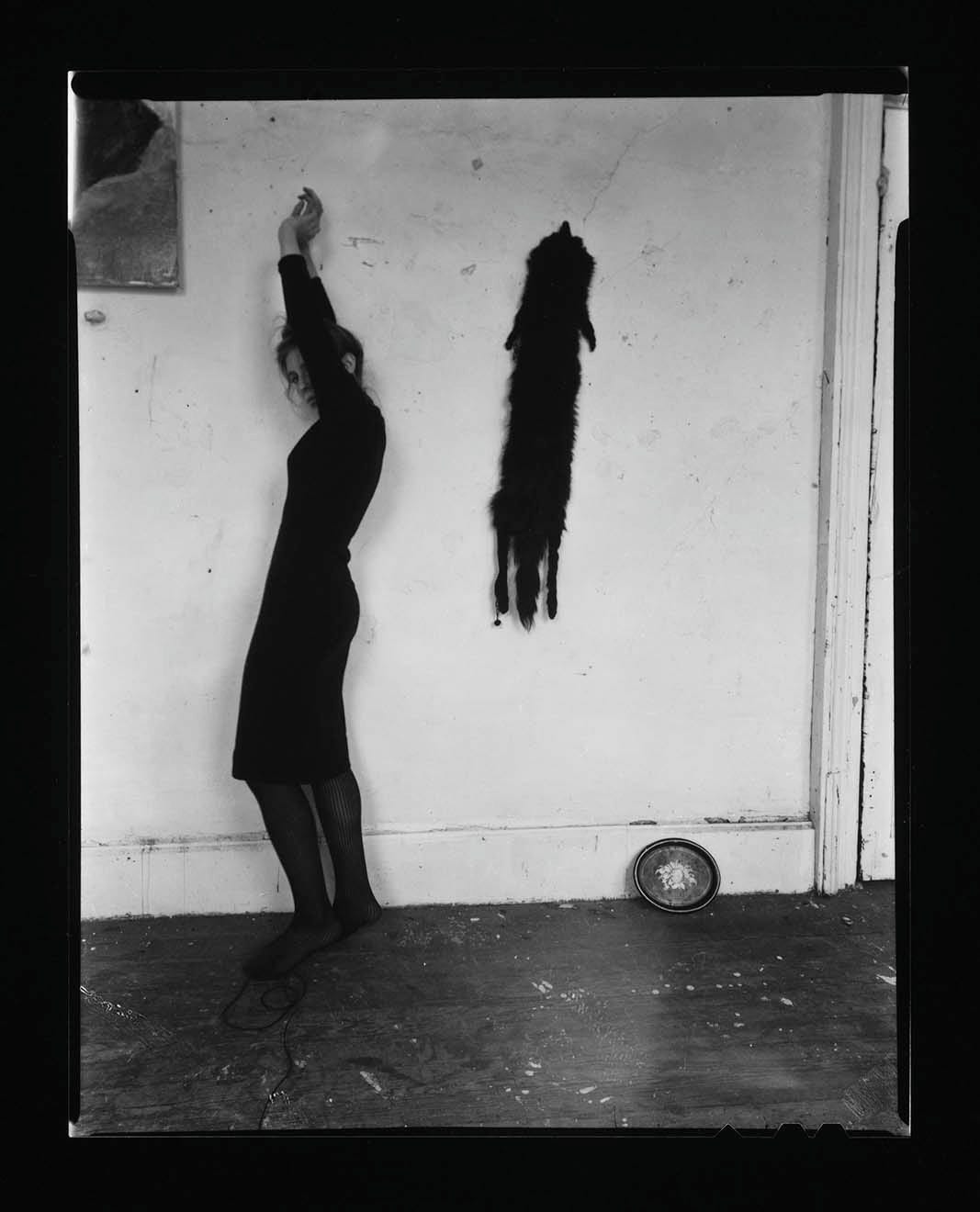

I experienced a true sense of aura when I first saw an exhibition of work by Francesca Woodman this past winter at the Columbus Museum of Art. Many of the photographs on view were familiar to me, having seen them reproduced in books many times. But experiencing them in person was singular—they were smaller than you would find in a publication and more clear. The depth of field, the contrasts, all in focus in a way that I’d never seen accurately reproduced in print publications. I could sense the presence in each image depicting Woodman’s form. There’s certainly something to be said for the aura of a printed photograph and the historic methods surrounding them.

I can’t remember how I was first introduced to the work of Francesca Woodman. As a woman in my early 20’s, full of all the complex feelings that come with that age, Woodman’s mysterious and moody medium format photographs seemed all consuming. I can vividly recall how sensual and haunting her work was to me during those days. This perceived aura, even through reproduced images, stirred in me my own transitional, youthful feelings and left me inspired to create in similar ways.1

Over time, the deeper I went in studying her work, the more I was drawn to the clothing and materials she surrounded her own body with.2 A favorite is when she photographed herself and several friends with Francesca masks, the only clue to who the real Francesca was being a pair of Mary Janes.

The shoes were typical staples in Woodman's wardrobe when she began photographing in Rhode Island, and became one of her identifying features. Her friend Edith Schloss reflected in 1995 upon her first meeting with Woodman: "She wore an old pinkish down parka over a long sprigged flower skirt and on her feet were those black … Mary-Jane's that gave girls of that period a duckfooted ballerina shape."

Little personal details always crept in to her work; in many photos she wears a silver ring on her pointer finger. I was so taken with this as a young woman, that after finding a silver ring at a yard sale, I’ve worn one on my own pointer finger for over a decade. Aura does not appear to us simply as a passing breeze but stirs up something close, in the soul.

The bulk of Woodman's work was produced in the 1970s and 1980s, a time notable in fashion history for changing aesthetics of dress in popular culture. Dress began to describe new, subversive social and gender norms, class breakdowns, and morphing societal traditions. Clothing also started to become more casual, sporty, and androgynous. What's striking about Woodman in relation to this change is that she often did not dress contemporary with her time; instead, she was fond of collecting and wearing vintage and antique clothing from the early 20th century, while sticking with traditionally feminine silhouettes.

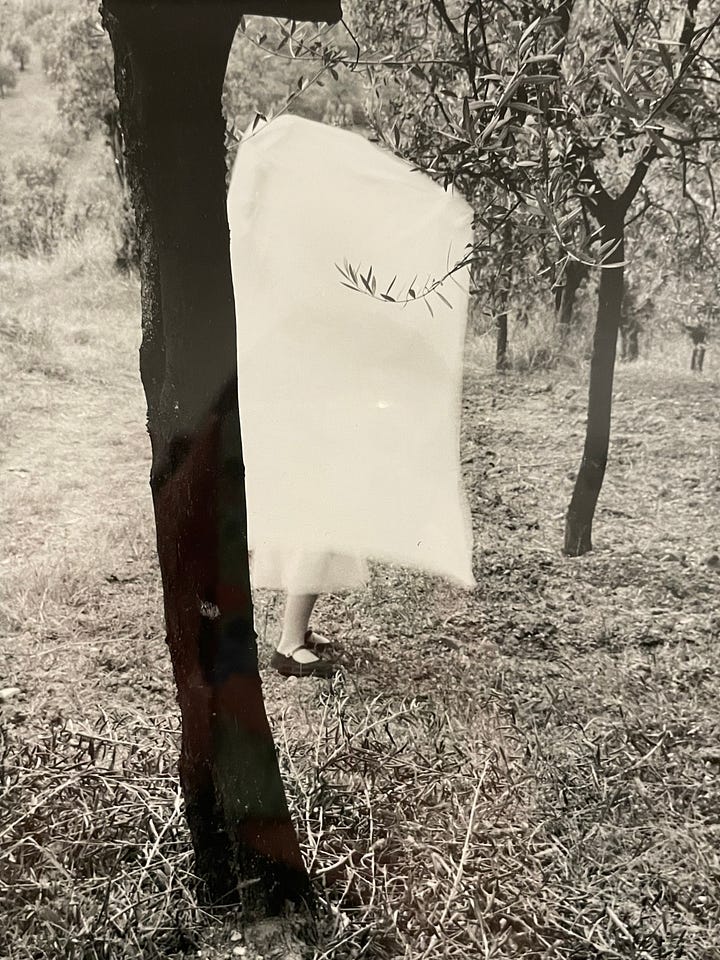

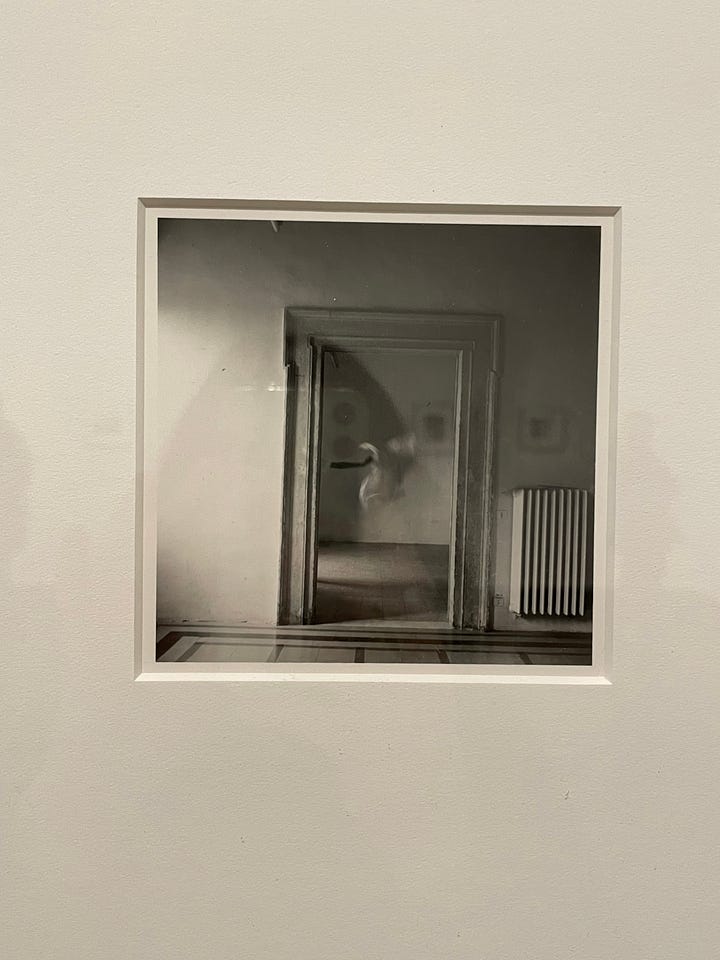

This is not to say that Francesca didn’t have an eye for fashion. She possessed a keen awareness for clothing and the way they communicated with the body and with viewers. In the late 70s/early 80s she produced a body of commercial fashion work while living in New York in hopes of working in the fashion industry. In contrast to her self-portraits in which she appeared (often) solo and predominately nude, her commercial fashion work employed friends and models to showcase clothing in vignettes both shocking and ethereal. Francesca kept the sets for most of these photographs in crumbling buildings similar to where she took her self-portraits. In these architectural contexts, the clothing she photographed seemed casual, soft, and mysterious, appealing in her own way to the sensibilities of her cultural moment.

Her work was ultimately not sought out by the fashion industry, but looking at these images through the lens of 2024, she was (clearly) ahead of her time. While one could argue parallels exist between Woodman’s fashion images and the work of photographers like Deborah Turbeville in the 1980s, Francescas’s fashion photographs convey the distinct eye and aura of the image maker.

In 2015, the Marian Goodman gallery in New York displayed Francesca’s fashion photography for the first time, and I encourage you to peruse the exhibition online. Curator Alison Gingeras wrote for the exhibition:

“Fashion had become a vital tool for both Woodman’s emerging artistic practice as well as for her self-definition. More than just providing props, fashion was a creative catalyst in her life and in her image making.”

I’ll be the first to admit that viewing Woodman’s work through a device screen is less than ideal. While Benjamin argues that reproduction can cause a lack of authenticity which negates the aura of a piece of art, I believe that the power of the photographic medium lies in simply being seen.3

The same can be said for fashion. The abundance of blockbuster fashion exhibitions in the last decade proves that the aura of static garments piques the imagination and connects with viewers. Fashion seems to inherently exist with (and profit from) aura as it is one of the few art forms that encapsulates the human body and is a driving factor in communicating cultural symbols.4

Reproductions then—the endless images on our devices—can be assistive in driving us to seek out physical artworks in order to experience and understand the fullness of the auras surrounding them. I’m so glad I sought out Woodman’s work in person, and I encourage those curious to do the same.

From the Woodman Family Foundation: The Lady of the Glove: Francesca Woodman and Surrealism

“The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity.”

A lot can also be said about the concept of involuntary memory and its role in the creation of aura. This article is helpful in understanding that, as well as the role of aura in branding.

These definitely reminded me of some of your photos from your early 20s! Also I know that silver ring you wear and can picture it clearly. ❤️